Since 1994, the number of cases of polio in the United States has dropped 96%. From 2006-2016, there have been zero cases. Vaccination schedules vary among states and territories.

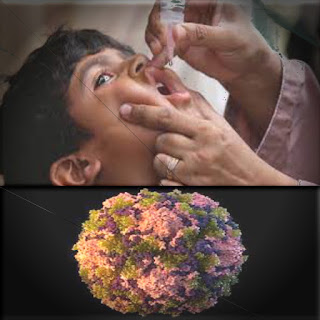

Polio in US, UK and Israel reveals rare risk of oral vaccine Think About

Dr Anthony Fuci led a team of scientists

who studied children born before and after the introduction of the polio

vaccine in the United States and Britain in 1955. Their findings showed no

evidence that the vaccine was causing any problems. But if parents had their

own reasons for refusing the vaccine - religious beliefs or political views,

for example - then they could put others at risk. The study looked at nearly

300 000 babies born between 1952 and 1963. In the US state of Indiana, where

about half of those born did not have the vaccination, the incidence of

paralysis due to poliomyelitis fell by 80% in the years since the vaccine came

out. But in some states, particularly in southern and western parts of America,

the number of cases rose sharply. There were also increasing numbers of cases

in the UK, although most were in adults. Dr Fuci said that while the research

was reassuring, he would still recommend the vaccination. Professor John

Oxford, chairman of the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health, said that

even though the results suggested that vaccines were safe, there should always

be a debate about whether people really understood the risks involved.

"It's certainly true that we would want to discuss with parents the

potential harm of giving them and their child the vaccine.

Oral polio vaccines

The oral polio vaccine (OPV) was introduced in the United States

in 1994 and replaced the killed polio vaccine (KPV). Since then, OPVs have been

shown to protect against disease-causing polioviruses while contributing to

herd immunity; however, some countries have experienced outbreaks of wild-type

poliovirus strains, including two cases of paralytic polio caused by serotype 2

in 2014. In 2015, the World Health Organization recommended that the use of

OPVs should be phased out worldwide in favor of the inject able vaccine, which

provides a higher level of protection.

Wild Polio virus

Wild poliovirus (WPV) circulates freely throughout many regions

of the world. WPV infects only humans and causes paralysis. There are three

types of poliovirus; type 1, type 2, and type 3. Type 1 and type 3 cause

disease in people, whereas type 2 does not. Of these three types, type 2 is

responsible for 99 percent of the polio infections in humans since 1988.

AFP surveillance

AFP surveillance identifies children who have had acute flaccid

paralysis. The term “acute flaccid paralysis” refers to weakness or paralysis

in any muscle group that appears suddenly and rapidly spreads from limb to

limb. Many different viruses may affect muscles. Common viral causes of AFP

include rotavirus; enter virus, mumps, measles, adenovirus, West Nile virus,

and Japanese encephalitis virus. All of these viruses except rotavirus can lead

to paralysis in young children. However, no single vaccine prevents them all.

Cases of polio

Between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2016, the number of

reported cases of polio in the U.S. decreased by 98% — from 644 cases to 13

cases. There were seven cases of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus

(cVDPV2), all in Nigeria. No cases have occurred in the Americas since April

2012.

Immunization schedule

Since 1994, the number of cases of polio in the United States

has dropped 96%. From 2006-2016, there have been zero cases. Vaccination

schedules vary among states and territories. The following table shows the

recommended immunization schedule based on the CDC guidelines:

6. Oral polio vaccine (OPV):

• First dose at 2 months old

• Second dose between 4-12 months

• Third dose between 12 – 15 months

Policies need to balance between protecting individual rights

while ensuring public safety. A recent outbreak of polio in the United States

caused panic among parents after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(CDC) recommended a three-month delay in routine vaccination that had been

implemented nationwide since 2014. Parents were worried about their children

being at risk of contracting polio if they did not receive the routine shots.

The CDC's recommendation was based on evidence showing that the

live virus vaccines used in the U.S. had caused cases of paralytic

poliomyelitis in some people who had received them. However, while it is true

that these vaccines have been linked to rare instances of paralysis in certain

individuals, the risk of serious side effects from the vaccine is extremely

low. In fact, only one case of severe adverse reaction occurred in over 10

million doses administered worldwide in 2016 alone.

In general, the risk of complications from any type of vaccine

is less than 1 per 100,000 doses. When compared to other commonly given

childhood vaccines (e.g., measles vaccine), the risks of the polio vaccine are

extremely small.

The vaccine contains weakened live viruses that replicate in the

body, causing immune system cells called T cells to attack the invaders,

thereby stimulating the production of antibodies against the viruses. The body

then reacts to these antibodies by producing more T cells. These T cells

destroy the infected cells before they spread the disease.

While the vaccine may cause minor reactions like fever and local

redness, swelling, and pain, these symptoms do not last long and the vast

majority of people recover without experiencing lasting damage? Serious side

effects, however, are exceedingly uncommon. According to the CDC, the incidence

of allergic reactions following immunization is less than 0.1 per 100,000 doses

and the rate of Gillian Bare syndrome, a rare neurological disorder affecting

nerves, is even lower: around 0.008 per 100,000 doses – well below what would

be considered acceptable risk levels.

Given the rarity of these conditions, there is no way to

definitively determine whether the polio vaccine causes them. As a result, the

CDC chose to err on the side of caution by recommending a temporary halt to the

routine administration of the vaccine until additional research could be done

to rule out the possibility of harm.

However, there is no scientific basis for the claim that the

polio vaccine causes paralysis. While several studies have suggested that the

live attenuated virus strains included in the vaccine may be associated with

cases of acute flaccid mellitus (AFM), two independent reviews of those studies

concluded that there was insufficient evidence to establish a causal

relationship.

These reports followed a study published earlier this year that

found no association between AFM and the use of the trivalent OPV (a

combination of three different types of attenuated viruses). That report was

conducted by researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

(NIAID).

An editorial accompanying the NIAID report stated that “there is

no direct proof that the vaccine strain causes AFM.” Since the publication of

that report, the World Health Organization has reiterated its position that

there is no link between the live attenuated virus vaccines and AFM.

With this latest outbreak, many parents remain concerned that

the benefits of receiving the polio vaccine outweigh the possible risks. But

the evidence suggests that the real problem lies elsewhere. The scare

surrounding this recent outbreak demonstrates just how easily misinformation

spreads online and underscores the importance of using reliable information

sources.

0 Comments